전국광, 모더니스트

이성휘

누워있는 조각가의 시간

지금으로부터 5년 전쯤 필자는 몇 장의 사진으로 인해 조각가 전국광의 작업을 알게 되었다. 그 사진은 사진작가 전명은이 병상에 누워있는 조각가(전국광의 동료)의 모습을 지켜보면서 오래전 사라진 조각가(전국광)에 대한 궁금함을 사진으로 담은 작업이었다. 그 당시 필자는 누워있는 조각가와 사라진 조각가를 바로 구분하지 못했고, 또 석고 모형인지 석조 완성품인지 바로 구분하지 못했다. 조각 사진에 섞여 있는 가시나무 사진도 자연물인지 바로 구분하지 못했다. 그 무지함은 조각이라는 장르에 대한 무지함이었을 테다. 이 전시는 그때의 무지함으로부터 출발하였고, 따라서 전명은의 사진 연작 <누워있는 조각가의 시간>(2016)에서 시작되었다고 말할 수 있다. 가까운 이들로부터 “너는 조각가의 손을 닮았다”는 말을 듣곤 했던 전명은은 오래전 사라진 조각가가 쓰던 작업실에서 그가 남기고 간, 선반을 빼곡히 채운 석고 모형들을 바라보다가 그것들을 촬영하였다. 이러저러한 형상의 덩어리들을 보면서 유난히 조각의 표면에 골똘했고, 그는 “조각가의 손끝은 덩어리의 표면 위에 닿았을 것이다. 덩어리의 표면은 덩어리의 내면을 가리킨다. 그렇다면 덩어리의 내면은? 조각가의 손끝에 또 다른 손끝을 갖다 대보면 덩어리의 내면이 가리키는 게 뭔 지 알 수 있을까?”[1] 하며 궁금해했다. 그 궁금증을 해결하기 위해 전명은이 촬영한 전국광의 조각 사진을 필자는 태블릿 화면으로 볼 수 있는 이미지 데이터의 형식으로 우선 마주하였다. 그리고 전명은의 사진이 빛/카메라로 조각 표면을 어루만지듯 조각의 표면에 닿았을 조각가의 손끝을 상상했다면, 공교롭게도 필자는 태블릿 화면으로 사진을 확대/축소하여 들여다보면서 액정을 사이에 두고 조각의 표면을 어루만질 수 있었다.

사진으로 먼저 만난 전국광의 조각을 오롯이 맨눈으로 대면하게 된 것은 지난 겨울에서야 이뤄졌다. 당연히 사진과 실견은 달랐으며, 사진과 작품 간의 스케일 차이 말고도 작업실 선반을 가득 채운 모형과 작품들이 결코 피하지 못한 세월의 흔적이 먼저 눈에 들어왔다. 그 시간의 괴리는 몇 차례 방문을 통해 눈을 익숙하게 만듦으로써 좁혀 나갈 수 있었는데, 그제서야 비로소 전명은이 사진으로 보여준 조각의 표면, 그 촉각이 느껴지기 시작하였다. 그리고 조각가의 손길이 조각의 표면 위에서 한 일을 상상해보게 되었다. 전에 전명은은 학창 시절 로댕 미술관을 방문했을 때 받은 인상을 인터뷰에서 말한 적이 있다. 그 자신도 한때 조각을 공부했던 전명은은 로댕의 미완성작들을 본 인상에 대해, “돌덩어리들이 있고 그 안에서부터 어떤 형상이 쑥 튀어나오는데 그걸 보면서 조각가가 하는 일은 형상을 만드는 게 아니구나, 조각가는 흙과 나무와 돌의 덩어리 안에서 숨죽이고 있던 그 형상을 찾아 나가는 거구나 라는 생각이 들더라”[2] 는 것이다. 비슷한 말을 미켈란젤로도 했다는 것 같은데, 조각가가 하는 일이란 덩어리 안에서 형상을 찾아내는 일이라니, 이때 그 형상은 마땅히 그 안에 있어야 하는 것을 말하는 것이리라.

매스, 적

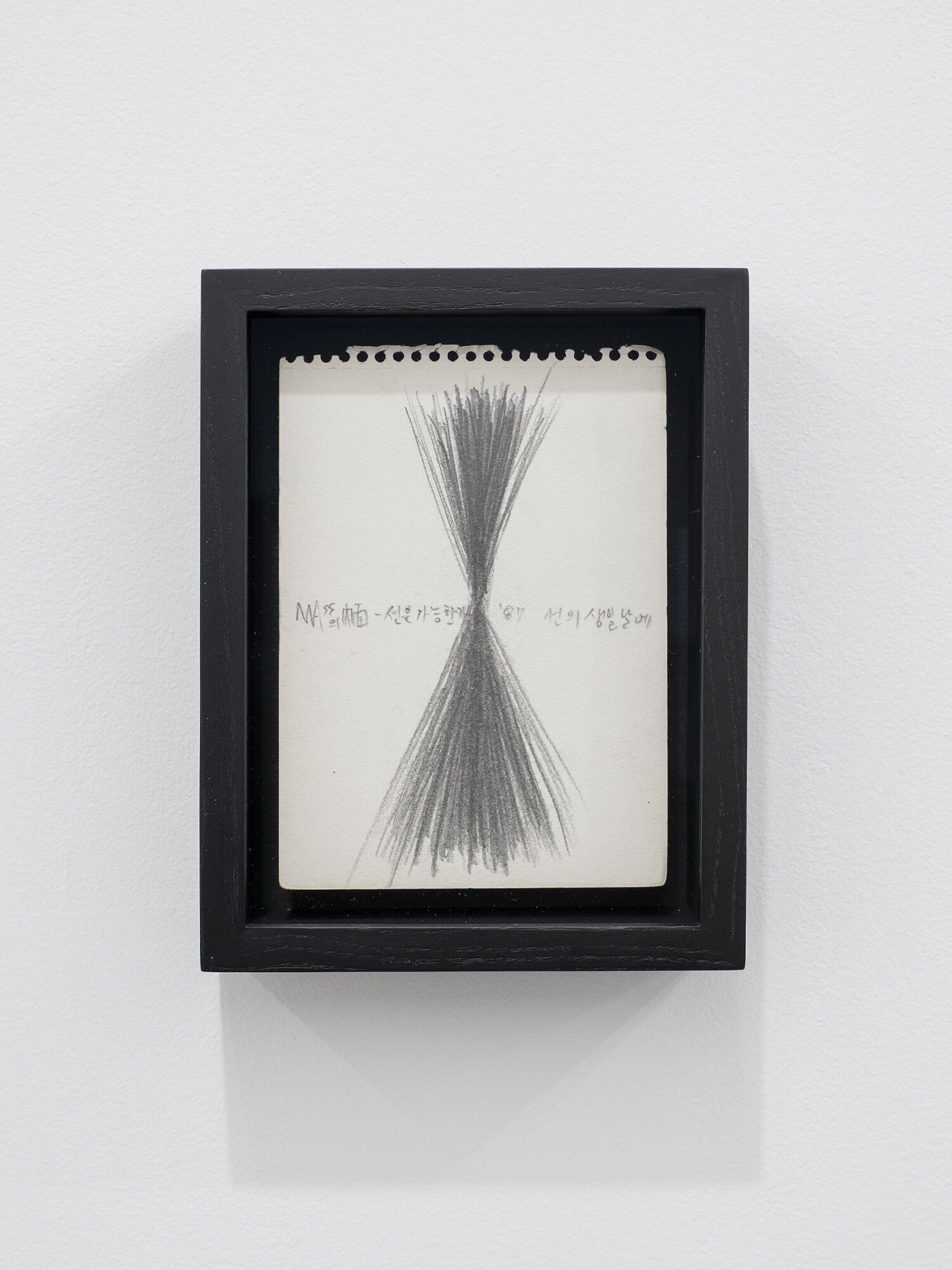

전국광 역시 조각의 형상은 마땅히 덩어리, 즉 매스 안에 있어야 하는 것으로 보았던 것 같다. 대학 시절 동료들과 함께 에스프리를 창립(1972)하기도 한 그는 졸업(1974) 후 본격적으로 활동을 시작하여 각종 공모전에 입상했을 뿐만 아니라 1990년 사고로 세상을 떠날 때까지 크고 작은 조각 작업들과 많은 드로잉들을 남겼다. 자신의 작업에 대한 태도나 열망에 대해서도 많은 글을 남겼다.[3] 그는 자신의 작업이 “형상이 지니고 있는 이미지에서보다는 매스 자체의 용적에서 그 근간이 이루어지도록 노력하였고, 동일한 규격의 물질이 임의의 조건에 의해 변이되어지는 물질의 변형 과정에 대한 매력에 심취하였다”고 하였다. 그 내용이 바로 ‘적(積)’ 시리즈이고 이때 그는 ‘적’이라는 말을 중의적으로 사용하여 ‘쌓기’라는 의미뿐만 아니라 적(enemy)의 의미 또한 포함시켰다. 그는 “나에게 가장 기분 언짢은 적은 바로 나이며 그의 적은 ‘매스’다…(중략)…(나는 매스와) 항시 충돌하며 싸우고 있으리라”고 하였다.[4] 그러는 한편, 자신에게 ‘겹겹이 쌓는 친구’, ‘이루어짐을 지켜보는 친구’와 같은 수식어구가 붙는 것에 대해서 굳이 부정하지 않겠다 하였지만 작가와 작품이 동시에 간단히 요약되어 버리는 상황을 불편히 여겼다. 그가 진정으로 바라는 바는 ‘다만 거짓 없이 있는 대로 드러나게 해주사’였고, 그래서 거짓없는 표현을 찾고자 하였다. 그는 양상으로서의 리얼리티가 아닌 본질로서의 리얼리티에 접할 수 있는 기회라면 그 표현방법이 쌓음이 아니라 허뭄일지라도 똑같이 심취할 것이며, 그것이 허무는 친구로 불려져 “쌓더니 허물더라”하는 조소가 있다해도 부끄러울 바가 없다고 까지 말하였다.[5] 즉 형상의 외양이 아닌 형상의 당위성을 매스에의 충돌을 통해서 추구한 것이다.

[1] 전명은, 『누워있는 조각가의 시간』, Float 6(서울: 헤적프레스, 2017), p.14.

[2] 전명은, 정희승, 「전명은–정희승: 대화」, 『사랑한다, 사랑하지 않는다』(서울: 하이트문화재단, 2017), p.254.

[3] 전국광은 1974년 홍익대 조소과를 졸업하고, 1977년 제2회 공간미술대상에 지원하여 <적–변이Ⅰ>(1977)로 조각부문 우수상을 수상하였다. 이후 1979년에 문예진흥원 미술회관에서 첫 번째 개인전을 개최하였다.

[4] 전국광의 작업노트에서 인용.

[5] ‘매스와 탈매스’에 대한 전국광의 메모 참조

자신이 어떠한 조각가인지에 대한 인식에 있어서도 전국광은 임의의 영감을 받아 형상을 창작하는 사람으로 보지 않았다. 그는 한 미술잡지에 기고한 글에서 조각가로서 자신이 “어떤 찰나 모종의 자극에 힘입어 일을 할 수 있었다기 보다는 느릿느릿 깨닫게 되는 순간순간의 여과에 의해서 조형 작업에 임해 왔음이 정직한 고백이라고 하였다. 자신이 영감에 의해 발전, 승화되는 예술인의 특성을 지닌 사례가 아닌 것 같고, 다만 게으르지 않게 이 일을 하다 보니 자기 확신이 조금씩 일어나며 경우에 따라 자부심 비슷하게까지 유도되어질 때도 있었다 하였다. 또, 그는 작업의 내적 동인을 자신의 능력을 넘는 내용으로는 의식은 물론이거니와 행위 또한 이룰 수 없다고 하면서, 그나마 느리게 성장되어진 조형의지가 실체(object) 앞에서 이루어 내는 조형의식에 대한 반응은, 교육에 의해서라기 보다 자연인으로서의 자기에서 나타나곤 한다는 것, 또 조그마한 물상 앞에서나 큰 사건 앞에서나 논리전개적인 사고가 아니라, 정서이입적으로 자연 물상을 흡수하게 되고 그 출발로 하여 조형 작품으로 성숙되어져 간다는 것으로 요약하였다.[6] 그러나 예술가의 본분에 대해서도 그는 많은 메모를 남겼고 자기확신을 위해 부단의 노력을 하겠다는 결심과 신념을 빈번하게 보여주었으며, 이를 실천하기 위해서 노력과 반성을 거듭 하였다. 생전 그가 달력 등에 남긴 작업 일정표를 보면 얼마나 쉬지 않고 성실하게 작업한 사람인지 짐작할 수 있다. 또 그렇게 반복적으로 스스로를 채근하고 다짐하며 남긴 글 중에는 작업의 변화 방향에 대한 고민도 담겨 있었다.

이번 전시 《전국광, 모더니스트》를 계획하던 초반에 필자는 전국광의 이전 전시들과 차별화를 꾀하고자 그의 후기작들에 초점을 맞춰 볼 셈을 한 적 있다. 그 요량으로 1986년 일본 교토 마로니에 화랑에서 열린 개인전 《매스의 내면 – 0.419㎥의 물상》을 기점으로 작업의 변화 양상을 살펴보고자 하였다. 그 이유는 마로니에 화랑 개인전에서 전국광은 동일한 용적이라는 조건에서 각각 다른 물질이 낳는 양태와 구조를 보여주려는 시도로, 나무, 흙, 테라코타, 직물, 노끈 등을 활용하여 좌대 위의 독립적인 오브제가 아닌 공간 설치에 가까운 전시를 선보였다. 당시 작가는 직접 쓴 전시설명문을 통해서 1980년대 초반부터 매스에 대한 해석 방법의 하나로 탈매스를 의식하고, 동시에 매스의 일루전(이를 테면 회화성이 내재된 조각)을 연구하며 중량과 중량감비, mass와 massive 등 이원적 허구성에 관심을 두어 일련의 작품을 제작하였다고 자신의 작업 세계를 개괄하였으나,[7] “향후 나의 매스에 대한 관심이 어떻게 변질되어질 것인가 하는 예감이 뚜렷하지 않은 현재, 매스의 내면이라는 명제를 떠나 나의 조형적 마음을 비우기 위해 이번 전시회를 가진다”고 하였다.[8] 당시 그는 어떤 갈등을 안고 있었을까? 사실 그의 작업은 처음부터 구상조각이 아닌 추상조각이었고 반복과 집적이라는 형식적 특징을 띠었지만, 연구자들은 서구 미니멀리즘과 연결하여 분석하지 않는 편이다. 서구 미니멀리즘이 보여준 산업소재의 몰개성, 작품의 즉자성, 사물로서의 사물, (저드의) 특수한 오브제와 같은 특징과 전국광은 거리가 멀었고, 어떤 측면에서는 형태의 구축자라고 할 수 있지만 러시아 아방가르드와는 거리가 멀다는 것이다. 오히려 전국광의 조각은 1970년대 한국미술이라는 조건에서 형성된 것으로 분석되는 바, 당시 선배 조각가들의 작품과 절충된 형식이기도 한, 기하학적인 형태 속에서 유기적인 구조체로서 스스로를 드러냈다는 것이다.[9] 다만, 마로니에 화랑 개인전에서 재료의 확장과 공간 설치에 가까운 시도를 한 것에 대해서 ‘설치를 통해서 자기완결성이 강하던 작품을 공간을 활성화하는 방향으로 전환시킴으로써 하나의 해결점을 찾으려 한 듯하다’고만 평하였다.[10] 전국광이 대학에 진학하여 조각에 대한 정규 교육을 받기 전 이미 선배 조각가들이 지휘하는 기념비적인 대형 조각품 제작 현장에서 재료의 물성부터 이를 다루는 기술까지 완벽하게 마스터 한 인물이라는 것은 주지의 사실이다. 그 기본기 때문에 그는 전형적인 조각의 습성을 벗어나는 실험에까지는 이르지 못했다고 평가받는 측면이 있다. 한국 현대조각사를 개괄하면서 최태만은 전국광이 조각의 전통을 고수하였지 조각의 전통을 파괴하는 전위예술가는 아니었다면서 그를 ‘현대적 고전주의자’라고 일컫기도 하였다.[11] 그런데 필자는 그가 충실한 기본주의자임은 인정하지만, 마로니에 화랑 개인전 즈음부터 분열과 균열의 양상으로 작업이 흘러가기 시작했음을 간과할 수는 없다.

[6] 전국광, 「일상과 예술의 길목」, 『미술세계』, 1986년 1월호, p.173.

[7] 위의 글.

[8] 전국광, 제4회 개인전 《매스의 내면 – 0.419㎥의 물상》의 작업설명 글에서 인용(1986.10).

[9] 최태만, 「적으로부터 매스의 내면으로」, 『Mass Mass Mass』(서울: 시월의책, 2006), pp.85-88.

[10] 위의 글, p.89.

[11] 최태만, 『한국 현대조각사 연구』(파주: 아트북스, 2007), p.400.

자유 – 나와 너희들 그리고 나들

“죽음 때문에 우리는 하루도 한가하게 지낼 수 없다”

위 문장은 에드워드 사이드의 책 『말년의 양식에 관하여』의 서두에 나오는 사무엘 베케트의 『프루스트』의 한 문장이다. [13] 이번 전시 《전국광, 모더니스트》에 대한 논의 초반, 필자는 전명은과 함께 사이드의 『말년의 양식에 관하여』를 기획의 단초로 삼은 바 있다. 전국광의 후기작들을 기존 작업들의 연장선상에서만 고찰하는 것은 충분치 않다는 생각이 들었고, 우리 역시 예술을 업으로 삼은 사람들로서 사이드가 천착한 ‘말년성’이라는 주제 자체에 대한 호기심이 함께 작용하였다. 사이드는 철학자 아도르노, 그리고 토마스 만, 리하르트 슈트라우스, 장 주네와 같은 예술가들의 말년성에 대해 고찰한 바 있는데, 그는 예술가들의 ‘늦음/말년성(lateness)’이 양식의 독특함을 통해 드러난다고 보고 이 주제에 오래동안 천착했다. 그는 베토벤에 대한 아도르노의 분석을 통해서 “말년의 양식은 현재 속에 거주하지만 묘하게 현재에서 벗어나 있다”며, “오직 몇몇 예술가들과 사상가들만이 자신의 전문가적 기술 역시 노화된다는 것을 인식할만큼 여기에 주목하며, 약해져 가는 감각과 기억을 동원하여 죽음을 마주해야 한다고 믿는다”고 말하거나, 토마스 만의 소설 『베네치아에서의 죽음』을 오페라로 옮긴 작곡가 벤자민 브리튼에 대해서는 주인공들의 결말을 조화로운 종합으로 끌어내지 않고 분열의 원동력으로서 시간 속에 풀어헤쳐 놓았다고 했다. 사이드는 연대기적으로 생의 말년에 이르러 얻게 되는 자연스러운 양식적 귀결에 관심을 가진 것이 아니라, 분열, 균열, 비타협적인 모순과 파국이 그대로 드러나는 것에 관심을 가졌다고 하지만, 그가 분석의 대상으로 삼은 예술가들은 한결 같이 양식적 성취와 변모를 충분히 누릴 수 있을 정도로 길게 활동한 작가들이다. 그에 비해 전국광의 활동 기간은 겨우 20년 정도로 모두가 전성기라고 볼만한 시기에 갑자기 세상을 떠났다. 그렇지만 전국광이야말로 ‘(죽음 때문에) 하루도 한가하게 지내지 않았던’ 조각가였던 것이다. 1980년대 중반까지 매스의 내면에 집중하던 그는 1980년대 후반에는 분열, 균열, 자기 모순을 더 거칠게 드러내기 시작하였다. 그는 1987년 9월의 메모에서 “나는 방출해 내놓는 듯한, 자기 정리되지 못한 작업 앞에서 환멸감을 느끼곤 한다. 끼우고 두들겨 맞추고 그 위에 껍질을 입힌 옷만으로서의 자기가 옷만 보이고 자신이 안보이기 때문이다. 그러나 내가 가장 불만스럽게 여기는 단면은 그러한 자유의지의 자신이 너무나도 없다는 것에 있다. 억제되어진 표정과 꼭 짜놓은 연출, 바로 그것을 때려 부수어야, 부셔버리고프다. 이빨도 안 들어갈 것 같은 그 기획되어져서야만 나오는 것 말고 조금은 헐렁한 어수룩한 기획 그것이야말로 그 윗길 아니겠는가”라고 하며, 억제된 자신이 아닌 자유의지에 대한 갈망을 드러내었다.[14] 또 1989년 2월에는 “Illusion의 새로운 국면을 제시한다. 시각적 중량감의 극대화 – 매어 단다, 허공에 띄워져 미동 한다. 한정공간의 확대 – 벽면에 3차원이 시각적 공간을 있게 한다. 이 공간안에 조각이 앉아 있도록 한다. 脫 Massive – 부재공간의 공간화, Volume이 삭제된 Massive”라는 메모를 남겼다.

후반 작업에 대한 전국광의 설명이나 변을 더이상 들을 수 없는 이 시점에 우리는 오롯이 그의 작품을 통해서 이를 추측해 볼 수밖에 없다. 이번 전시는 그의 활동 기간 전체를 고루 살필 수 있도록 유족 소장품 중에서 초기작부터 후기작까지 다양하게 출품작을 선택하였다. 알루미늄 작업인 <매스의 내면>(1980)은 처음으로 작품 수복 과정을 거쳤으며, <자유 – 일백팔개의 치성탑>(1989)이나 <자유 – 나와 너희들 그리고 나들>(1989)은 그가 남긴 거의 마지막 작업에 해당한다. 투명 아크릴의 단면을 날카롭게 절단, 조립하여 모빌 형식으로 매단 <매스의 내면>(1986)이나 비닐 테이프를 붙여 만든 <매스의 내면 – 해면>(1985)은 그가 실험하고자 한 일루전이 무엇이었을까 상상케 한다. <자력 – 0.027㎥의 공간>(1986)은 작가가 생존시 시도한 설치 방식을 처음으로 다시 재현해 본 것이다. 그 형태가 작가의 기록 사진과 동일하지는 않더라도 공간의 모서리 양 벽을 지탱하는 어떤 힘의 표현이기를 원했다. 어쩌면 우리는 사이드의 ‘말년성’이라는 키워드를 그의 후반 작업에 굳이 대입시키지 않아도 될지 모른다. 그는 어떤 균열, 분열, 변화의 한 순간에 아름답게 멈춰 서 있고, 우리의 전시는 그 지점에서부터 다시 시작했을 뿐이다.

[12] Samuel Beckett, Proust (London: Calder, 1965), p.17(에드워드 사이드, 장호연 옮김, 『말년의 양식에 관하여』(서울: 마티, 2012), p.13에서 재인용).

[13] 에드워드 사이드는 『말년의 양식에 관하여』의 집필을 완결하지 못하고 갑자기 세상을 떠났기 때문에 이 책은 그의 사후에 가족과 지인들이 출간했다. 책의 편집자인 마이클 우드가 서문을 썼는데 그가 사무엘 베케트의 『프루스트』를 인용하였다.

[14] 전국광, 『Mass Mass Mass』(서울: 시월의책, 2006), p.279.

전국광 全國光 (1945-1990)

조각가 전국광(1945-1990, 서울 출생)은 쌓고 반복하고 해체하고 재건하는 행위를 통해 ‘매스’가 지닌 조각 언어의 본질을 탐구하였다. 매스의 가능성을 찾는 동시에 그 한계에 직면했으며 매스의 부피와 무게로부터 벗어나는 자유를 모색하기도 했다. 작품 활동 기간은 이십 년이 채 되지 않지만, <적(積)> 연작과 <매스의 내면> 연작을 중심으로 하는 수백 점의 조각과 평면 작업을 남겼다. 홍익대 조소과를 졸업하고(1974, 서울), 문예진흥원 미술회관에서의 첫 번째 개인전(1979, 서울) 이후, 마로니에화랑(1981/1986, 교토, 일본), 관훈미술관(1983, 서울), 표화랑(1988, 서울) 등에서 다섯 차례의 개인전을 열었으며, 사후에는 표화랑(1991/1995, 서울), 가나아트센터(2000/2018, 서울), 모란미술관(2006, 서울), 성곡미술관(2011, 서울) 등에서 여섯 차례 회고전이 개최되었다. 제2회 공간미술대상 조각부문 우수상(1977, 공간화랑, 서울)과 제30회 국전 대상(1981, 국립현대미술관, 과천)을 받았으며, 국제 석조각 심포지엄에 한국 대표로 참가하였다(1988, 아지초, 일본). 국립현대미술관, 서울시립미술관, 부산시립미술관, 대전시립미술관, 대구미술관, 경기도미술관, 경남도립미술관, 전북도립미술관, 전남도립미술관, 포항시립미술관, 멕시코 현대미술관(멕시코시티, 멕시코), 교토 시립예술대학(교토, 일본) 등에 작품이 소장되어 있다.

개인전

2022 전국광, 모더니스트, 웨스, 서울

2018 매스, 가나아트센터, 서울

2011 매스의 내면–전국광을 아십니까, 성곡미술관, 서울

2006 Mass Mass Mass, 모란미술관, 경기도

2000 돌에 핀 석화, 전국광, 가나아트센터, 서울

1995 전국광: 5주기 드로잉전, 표화랑, 서울

1991 전국광: 1주기전, 표화랑, 서울

1988 전국광, 표화랑, 서울

1986 매스의 내면 – 0.419㎥의 물상, 마로니에 화랑, 교토, 일본

1983 Mass and movement, 관훈미술관, 서울

1981 전국광, 마로니에 화랑, 교토, 일본

1979 전국광, 문예진흥원 미술회관, 서울

주요 단체전

2019

한국 근현대조각 100주년:한국 현대조각의 단면, 서소문성지역사박물관, 서울

2018

수직충동, 수평충동, 대구미술관, 대구

경기천년 도큐페스타: 경기아카이브 지금, 경기상상캠퍼스, 수원

2016

달은, 차고, 이지러진다: 국립현대미술관 과천 30년 특별전, 국립현대미술관, 과천

2015

사물의 소리를 듣다: 1970년대 이후 한국 현대미술의 물질성, 국립현대미술관, 과천

2013

추상은 살아있다, 경기도미술관, 안산

2010

마침표, 장흥아트파크, 양주

2009

한국현대조각의 흐름과 양상, 경남도립미술관, 창원

2007

작품의 재구성, 경기도미술관, 안산

2004

한국현대작가초대전, 서울시립미술관 남서울분관, 서울

2001

요절과 숙명의 작가, 가나아트센터, 서울

1990

청화랑 초대전, 청화랑, 서울

부산환경조각전, 해인화랑, 부산

현대미술초대전, 국립현대미술관, 과천

1989

파리 서울 방법전, 미술회관, 서울

한국조각대전, 선화랑, 서울

한국현대미술전, 현대미술관, 멕시코시티, 멕시코

현대미술초대전, 국립현대미술관, 과천

중진조각가 16인전, 동숭미술관, 서울

1988

국제 석조각 심포지움, 아지초, 카와켄, 일본

미노카모 조각 심포지움, 미노카모, 일본

현대미술제, 국립현대미술관, 과천

현대조각가 16인전, 동숭미술관, 서울

조각3인전, 표화랑, 서울

1987

한국현대미술전 80년대의 정황, 베니화랑, 교토, 일본

현대조각 10인 초대전, 일갤러리, 서울

한국현대조각의 오늘, 토탈미술관, 서울

제8회 International Impact Art Festival, 시립미술관, 교토, 일본

1986

오늘의 현대조각 10인전, 바탕골미술관, 서울

아시아현대미술전, 국립현대미술관, 과천

한국현대미술 어제와 오늘전, 국립현대미술관, 과천

제7회 International Impact Art Festival, 시립미술관, 교토, 일본

제5회 한일현대조각회전, 후쿠오카시립미술관, 후쿠오카, 일본

1985

한국미술전, 그랑팔레, 파리, 프랑스

파리 서울 방법전, 미술회관, 서울

제6회 International Impact Art Festival, 시립미술관, 교토, 일본

제4회 한일현대조각회전, 미술회관, 서울

1984

현대미술초대전, 국립현대미술관, 서울

젊은작가 23인 초대전, 관훈미술관, 서울

영남대학교 미술대학 조소과 교수 작품전, 예맥화랑, 대구

제5회 International Impact Art Festival, 시립미술관, 교토, 일본

제3회 한일현대조각회전, 후쿠오카시립미술관, 후쿠오카, 일본

1983

30대 조각가전, 청년미술관, 서울

한국현대미술전, 비스콘티아홀, 밀라노, 이탈리아

서울국제드로잉전, 미술회관, 서울

대구미술 ‘83전, 수화랑, 대구

제4회 International Impact Art Festival, 시립미술관, 교토, 일본

제2회 한일현대조각회전, 미술회관, 서울

1982

제5회 인도 트리엔날레, 뉴델리, 인도

28인의 이미지전, 수화랑, 대구

제8회 서울현대미술제, 미술회관, 서울

제3회 International Impact Art Festival, 시립미술관, 교토, 일본

제1회 한일현대조각회전, 후쿠오카시립미술관, 후쿠오카, 일본

1981

제1회 부산청년비엔날레, 공간화랑, 부산

오늘의 상황전, 관훈미술관, 서울

제14회한국현대조각회전미술회관

제5회 에꼴드서울전 국립현대미술관, 서울

국립현대미술관 건립기금 조성전, 명동화랑, 서울

1980

아시아 현대미술전 II, 후쿠오카시립미술관, 후쿠오카, 일본

제13회 한국현대조각회전, 미술회관, 서울

오늘의 방법전, 관훈미술관, 서울

한국판화드로잉대전, 국립현대미술관, 서울

조각 11인전, 미술회관, 서울

현대조각야외전, 신라호텔, 서울

한국현대회화조각연립전, 관훈미술관, 서울

1979

제4회 에꼴드서울전, 국립현대미술관, 서울

한국미술 오늘의 방법전, 미술회관, 서울

제5회 서울현대미술제, 국립현대미술관, 서울

1978

제10회 한국현대회화조각연립전, 국립현대미술관, 서울

1977

제3회 대구현대미술제, 시민회관, 대구

제2회 공간미술대상전, 공간화랑, 서울

제8회 한국현대조각회전, 명동화랑, 서울

제9회 한국현대조각회전, 국립현대미술관, 서울

1976

제4회 한국미술청년작가회전, 전일미술관, 광주

제3회 한국미술청년작가회전, 국립현대미술관, 서울

한국미술청년작가회 해외전, 필라델피아, 미국

제1회 부산현대미술제, 부산시민회관, 부산

1975

한국미술청년작가회 야외작품 발표회, 안면도 꽃지해변, 충청남도

제2회 한국미술청년작가회전, 탑미술관, 부산

제1회 서울현대미술제, 국립현대미술관, 서울

1974

한국미술청년작가회 창립전, 미술회관, 서울

제4회 에스쁘리 동인전, 명동화랑, 서울

제1회 서울 비엔날레전, 국립현대미술관, 서울

제2회 앙데팡당전, 국립현대미술관, 서울

1973

제3회 에스쁘리 동인전, 신문회관, 서울

1972

제2회 에스쁘리 동인전, 명동화랑, 서울

에스쁘리 창립전, 국립중앙공보관, 서울

제1회 앙데팡당전, 국립현대미술관, 서울

수상

1981 제30회 대한민국미술전람회(국전) 대상, 국립현대미술관1980 제29회 국전 특선, 국립현대미술관

1979 제28회 국전 특선, 국립현대미술관

1978 제27회 국전 입선, 국립현대미술관

1977 공간대상 조각 부분 우수상, 공간화랑

1977 제26회 국전 입선, 국립현대미술관

1976 제25회 국전 입선, 국립현대미술관

1975 제24회 국전 입선, 국립현대미술관

1969 제18회 국전 입선, 국립현대미술관

주요 작품소장처

국립현대미술관, 과천

서울시립미술관, 서울

부산시립미술관, 부산

대전시립미술관, 대전

대구미술관, 대구

경기도미술관, 안산

경남도립미술관, 창원

전북도립미술관, 완주

전남도립미술관, 광양

포항시립미술관, 포항

모란미술관, 남양주

멕시코 현대미술관, 차풀테펙공원, 멕시코시티, 멕시코

교토 시립예술대학, 교토, 일본

아지초, 카와켄, 일본

제주조각공원, 제주

국립현대미술관 미술은행, 과천

서울교육문화회관, 서울

신라호텔, 서울|

리베라호텔, 서울

한국공항터미널, 서울

외환은행 본점, 서울

주택은행 본점, 서울

전국광, 모더니스트 (Chun Kook-kwang, a Modernist)

2022년 3월 12일 ~ 4월 8일

참여작가: 전국광

기획: 이성휘 (WESS 멤버, 하이트문화재단 큐레이터)

도움: 전명은

그래픽 디자인: Studio Cymbal

작품수복: 장준호

출품작: 전국광의 1970-80년대 조각 및 드로잉 작업 22점, 작업 메모와 사진기록물 다수

Chun Kook-kwang, a Modernist

Sunghui Lee

Le repos incomplet: the Time of a Lying Sculptor

About five years ago, I first came to learn about Chun Kook-kwang’s work by means of a few photographs by photographer Chun Eun. Her visit to a sculptor in his sickbed (who was a colleague of Kook-kwang) triggered her curiosity about another sculptor (Kook-kwang), who was by then long gone. Then, I was not able to distinguish either the lying sculptor from the gone or whether the work depicted was a gypsum model or completed stonework. I couldn’t even tell whether the picture of a thorn amongst other pictures of sculpture was real or not. That ignorance of mine was probably parallel to my ignorance of the genre of sculpture. This exhibition started from the ignorance of that time; therefore, from Eun’s series Le repos incomplet (2016), I would say. From people close to her, Eun used to hear that she “took after the sculptor’s hands.” Long after the sculptor’s death, as she was observing gypsum models that filled up the shelves in his old studio, she decided to photograph them. Capturing those masses in different shapes, she delved into the surface of his sculpture specifically. She pondered, “The sculptor’s fingertips must have touched on the surface of mass. Its surface hints at the inner mass. Then, what does the inner mass hint on? If I bring my fingertips to his, could the indication of inner mass be revealed?”[1] As an attempt to answer the question, Eun photographed Kook-kwang’s sculptures. I received those in the form of image data browsable on a tablet in the first place. Eun’s photography caressed the surface of his sculpture by means of the light traversing her camera, trying to imagine the sculptor’s fingertips touching sculptures. As for me, when I zoomed in and out the pictures on the tablet screen, I could unexpectedly touch the surface of the sculpture, scintillating below the liquid crystal panel.

It was only last winter when I could finally encounter Kook-kwang’s sculpture face to face, which I had first seen as images. The real perception undoubtedly differed from the pictures. Not only due to the difference of scale between the picture and the work but also the sight of inevitable traces of time accumulated on the models and works, densely occupying the studio shelves. This discrepancy of time could be narrowed down through repeated visits that eventually accustomed my view of them. As my perception became more focused, I could actually sense the palpability of their surface as captured in Eun’s photography. This led me to imaginations of the work of the sculptor’s hand that must have manifested on the surface of sculpture. Eun once spoke in an interview about impressions she got when she visited the Musée Rodin in Paris. Still a sculpture student back then, looking at the unfinished works by Rodin and how “the figures bulged out abruptly from the masses of stone,” Eun realized that “the task of a sculptor is not to carve out any figure but to discover it hiding inside the masses of soil, wood and stone.”[2] Michelangelo should have said something similar, that the task of the sculptor is to discover a figure from a block of stone. Here, I believe the figure must indicate something that ought to dwell in that ‘inside.’

[1] Chun Eun, Le repos incomplet, Float 6 (Seoul: Hezuk Press, 2017), 14.

[2] Chun Eun, Heeseung Chung, “Chun Eun–Heeseung Chung: A Conversation,” I Love You, I Love You Not (Seoul: HITE Foundation, 2017), 254.

Mass, Amass/Enemy

Likewise, Kook-kwang seems to have considered the figure of a sculpture dwelling within the mass. As a university student, he founded Group Esprit (1972) with his fellow students. After graduation, he launched his career winning various prizes and produced large and small sculptures as well as numerous drawings until his death in an accident in 1990.[3] He also left plenty of writings about his attitude and aspiration toward his work. He wrote that his work is “based on the volume of the mass itself, rather than the image of a figure; it is induced by the process of material modification, how a standardized material transits to something else under certain conditions.” His Amass series reflects this idea, where he plays with the Korean word of jeok, indicating both “accumulation” and “enemy.” He wrote, “The most distressing enemy of mine is myself, and his enemy is ‘the mass’ (…) I will always clash and struggle with it.”[4] On the other hand, while he was not completely denying the attributes endorsed to him such as “the layering artist” or “the one who contemplates on the accumulation,” he still felt uneasy about the fact an artist and his work could get rendered into simple labels. He only yearned for “a bare discovery with no deception” and therefore, sought for a truthful expression. He even asserted, to achieve the chance of touching the reality not as a visual feature but its existential essence, he would be equally fascinated by expressions of dispersion instead of accumulation and would shamelessly confront the critics that might accuse him to be the ‘dismantler,’ who “accumulates, then to demolish it.”[5] In other words, clashing with the mass, he aimed to reach the figure’s essence instead of its appearance.

In his awareness as a sculptor as well, he didn’t consider himself as the creator of figures motivated by arbitrary inspirations. In an article he wrote for an art magazine, he candidly confessed that he “undertook his artistic work through repeated moments of filtering slow recognitions, rather than being triggered by ephemeral and random stimulation.” He also said not to be an example of artistic development and sublimation prompted by inspirations but just didn’t neglect his work, which led him to gradually growing confidence or even pride at times. Moreover, he described that the inner impetus for his work was activated by neither consciousness nor the act that lies beyond his own capacity. If ever, his artistic response toward the realization of an object, deriving from slowly growing motivation, was related to himself as a natural person rather than his educational background. He summarized, be it confronting a small object or a large event, he absorbed natural objects not through logical thinking but affective projection; starting from there, it would mature as an artistic product.[6] At the same time, he also left many notes about the duties of an artist, often revealing his resolution and belief in continuous struggles for confidence. To achieve such artistic practice, he strived and reflected again and again. Reading his schedules marked on the calendar, etc. we can see how committed and ceaseless he worked. In the writings he left, he pushed and engaged himself, while delving into possible new directions for his work.

Conceiving Chun Kook-kwang, a Modernist, I was planning to highlight his late work to differentiate this exhibition from previous ones where his work was presented. As an attempt, I was willing to detect the changes in his work after Inner Mass – 0.419㎥ of Matter, his solo exhibition held at Maronie Gallery, Kyoto, Japan in 1986. It was because he presented a quasi-installative exhibition at the gallery instead of object-centered display on pedestal, under the condition of giving various material of wood, soil, terracotta, fabric and twine the same volume––with the aim to expose the differing aspect and structure as per each material. At that time, the artist outlined his oeuvre to have started since early 1980 from becoming aware of ‘meta-mass’ as a method of interpreting the mass. At the same time, he studied the illusion suggested by the mass, the painterly innate to sculpture for example. His works were “created from the interest in the fictive duality of volume and voluminous proportions, the mass and the massive, etc.”[7] However, he continued, “currently, anticipation of how my further interest in mass might shift is still foggy. I open this exhibition purely to pour out my desire for the form, departing from my own propositions on inner mass.”[8] What conflicts were concerning him? Indeed, his sculpture was rather abstract than figurative from the beginning and employed repetition and accumulation as its formalistic character. Yet critics did not commonly analyze him in connection to the western Minimalism: its characteristics such as the sterile aesthetic of industrial material, literality of works, handling of object as object and specificity of object (à la Donald Judd) were far from Kook-kwang’s practice; on the other hand, he could have been seen as a constructivist of forms, yet he was also distant from Russian avant-garde. Instead, it was plausible to analyze Chun’s sculpture to have developed under the influence of Korean art in the 1970s, as organic constructions emerging from geometric figures, a form complementary to his forerunning colleagues’ works.[9] About his experimentation with an expanded range of material and semi-installative space, the critical analysis concluded, “Chun seemed to suggest his own solution by shifting the self-enclosed work to installation through activating the space.”[10]

It is widely known that Chun had perfectly mastered materiality of matters and technique of handling them even before his admission to the university and regular sculpture education, on sites of sculpture production in monumental scales guided by professional sculptors. Apparently due to the deeply learned skills, some evaluated his sculptural experiments to be still anchored to conventional sculptural habits. Taeman Choi, who summed up the history of Korean modern sculpture, called Chun a “modern classicist” who adhered to sculptural traditions rather than an avant-garde who destroyed it.[11] However, while I agree he was true to fundamentals of sculptural practice, I cannot ignore the deviation of his work toward dissociation and fragmentation starting to manifest around the time of his solo exhibition at Maronie Gallery.

[3] Kook-kwang graduated from the Sculpture Department at Hongik University in 1974, applied to the 2nd GongKan Art Contest with Amass–Mutation Ⅰ (1977) and won the Excellence Award in the sculpture section. Later in 1979, he held his first solo exhibition at Arko Art Center.

[4] Quote from Chun Kook-kwang’s notes.

[5] Refers to Chun Kook-kwang’s notes on Mass and Meta Mass.

[6] Chun, Kook-kwang, “On the Verge of Daily Life and Art,” Misulsegye, January 1986, 173.

[7] Chun, Kook-kwang, work description, Inner Mass: an Object of 0.419 ㎥, Chun’s fourth solo exhibition (October 1986).

[8] Ibid.

[9] Taeman Choi “From Amass to Inner Mass” Mass Mass Mass (Seoul: Siwalbook, 2006), 85-88.

[10] Ibid., 89.

[11] Taeman Choi, History of Korean Modern Sculpture (Paju: Artbooks, 2007), 400.

Freedom – I, You and ‘I’s

“Death has not required us to keep a day free.”[12]

This line is from Proust by Samuel Beckett, quoted in the introduction of Edward W. Said’s On Late Style.[13] At the beginning of curatorial discussions on Chun Kook-kwang, a Modernist exhibition, Eun and I took On Late Style as our lead. Considering Kook-kwang’s late work only as an extension of previous work didn’t seem to be sufficient to our eyes. Furthermore, we wished to satiate our curiosity as practitioners of art about ‘lateness,’ a theme with which Said was much occupied. Said investigated the lateness in cases of philosopher Theodor W. Adorno, writers Thomas Mann and Jean Genet, and composer Richard Strauss. He asserted that the lateness of an artist is revealed through the uniqueness of style and investigated the subject over a long period. From Adorno’s analysis of Beethoven, he infers, “Late style is in but oddly apart from, the present” and “only certain artists and thinkers care enough about their métier to believe that it too ages and must face death with failing senses and memory.”[14] On composer Benjamin Britton who transferred Thomas Mann’s novel The Death in Venice into an opera, he wrote, “[Britton] does not bring about their harmonious synthesis. As the power of dissociation, he tears them apart in time.”[15] Said claims not to be interested in the stylistic harmony and resolution naturally gained toward the end of life in chronological order but in dissociation, fragmentation, unsolved contradiction and catastrophe. However, the objects of his analyses are artists who lived long enough to flourish in stylistic achievements and modifications. In contrast, Kook-kwang died abruptly in the midst of undeniably prime years of his career of about mere twenty years. Still, as a sculptor, he was a real example of those whom “Death has not required to keep a day free.” Whereas he focused on inner mass until the mid-1980s, toward the end of the decade, he started to address his notions of dissociation, fragmentation and self-contradiction in a bolder way. In a note from September 1987, his yearning for liberation instead of oppression of the self is apparent: “I often face my disillusion, facing works that are simply released, lacking self-definition. I am faced with a costume; a peel over my inserted, struck and polished self. That costume covers and makes myself invisible. The most deficient aspect is the complete absence of my free-willing self. Reserved expression, tightly staged––I desire to destroy this more than anything. Neither sleek nor highly designed, but something that is rather loose and clumsy; that would be the true next level.”[16] And in February 1989, he left the following note: “Propose a new moment of illusion. Maximize the visual volume––hanging, floating in the void, in subtle movement. Expand limited space––the three-dimensional on the wall will create a visual space; within this space, I will place my sculpture. The meta-massive––spatialization of the absence; the massive with no volume.”

At this point, as we can no longer hear his explanation or statement about late work, we can only assume his voice from his work solely. The exhibited works are selected from the collection of his family, ranging from formative to late years, with the aim to present the entire development of his artistic practice. For this, work in aluminum Inner Mass (1980) was restored for the first time, while Freedom: Pagoda of One Hundred and Eight Wishes (1989) or Freedom: I, You and ‘I’s (1989) mark one of the very last works he made. Inner Mass (1986), a hanging mobile assembling sharply cut acrylic panels or Inner Mass: Sea Surface (1985) in vinyl tape layers animate our imagination of “illusions” he was about to experiment with. Magnetic Force: 0.027㎥ Space (1986) is the first reenactment of the installation method he had realized after different attempts. Its shape might differ from his documentation pictures, yet we wished it to become an expression of power that supports the spatial edges of two walls. Perhaps we wouldn’t even need to project Said’s keyword of “lateness” to his late work, because he stands still in the beauty of the moment of certain dissociation, fragmentation and change; and our exhibition has only just resumed from that point.

[12] Samuel Beckett, Proust (London: Calder, 1965), 17.

[13] Because of Edward W. Said’s sudden death before finalizing the writing of On Late Style, his family and colleagues published the book posthumously. The editor in charge, Michael Wood, wrote the introduction, who also quoted Samuel Beckett’s Proust.

[14] Edward W. Said, On Late Style: Music and Literature Against the Grain (New York: Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, 2008), 24.

[15 Ibid., 160.

[16] Chun Kook-kwang, Mass Mass Mass, (Seoul: Siwalbook, 2006), 279.

Chun Kook-kwang, a Modernist

2022. 3. 12 ~ 4. 8

Artist: Chun Kook-kwang

Curated by : Sunghui Lee (WESS, HITE Collection Curator)

Support: Eun Chun

Graphic design: Studio Cymbal

Art restoration: Junho Jang

Art works: Sculpture, drawings; 22 pieces and memos, photos etc from 1970-1980 by Chun Kook-kwang

Related publication

Read More →